I saw Les Miserables at Village Theatre opening night.

I had a good time, so let me say some good things first: The set is fantastic, and a lot of the performances were wonderful (I know Kate Jaeger, but don’t think its bias speaking when I say that she, Nick DeSantis and Victoria Ames Smith made for some of the strongest Les Miserables scenes I’ve ever seen staged). Everyone involved should be proud of the piece. Go see it, and you’ll almost certainly be impressed.

Here’s the rub : I spent the whole time marveling at the technical spectacles of the show. And that’s the problem.

I was rarely very emotionally invested, and when the revolution came, it seemed compelled by the needs of the show than the needs of the characters. I barely paid attention to “les miserables”, because I was so distracted by the machinations of the stage. It was as if the title characters of the piece didn’t quite fit in with the level of production, so they were either cleaned up, or shipped out of the city so a nicely produced revolution could take place.

Of course, that’s almost always a problem with the musical version Les Miserables, and I still consider it one of my favorite musicals, but it certainly doesn’t achieve an ounce of what I think Victor Hugo set out to achieve when he wrote the book.

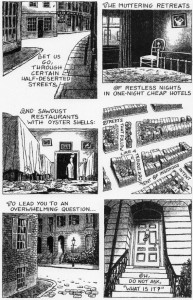

Today, I ran into another example of this pattern in art, where excess robs the audience of their ability to connect, when Slate posted this comic versionof T.S. Eliot’s poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” by Julian Peters.

I like artist, and I love this poem, so it caught my attention when I didn’t like the piece as a whole.

Poetry has a bad reputation for being inaccessible, which is too bad, because the core of the art is the opposite. How does the artist make their experiences and feelings accessible to the reader?

Consider the lines depicted to the right, but alone, without the image:

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells:

Streets that follow like a tedious argument

Of insidious intent

To lead you to an overwhelming question…

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Let us go and make our visit.

Good poetry depends on the reader imagining the images described. And imagination is not creation, it is re-creation. The reader recreate the visual images out of their own experiences. When I read “certain half-deserted streets” I create the image out of the certain half-deserted streets in my memory, and suddenly I’m there.

When you hand me the image, I’m robbed of the process. These are somebody else’s half-deserted streets. When I read the comic, I notice how clever it is that “streets that follow like a tedious argument of insidious intent” winds through the illustrated city, but when I read the poem, I actually connect to the memories about tedious arguments I’ve been part of, and I feel the connection.

At any rate, if I were to stage Les Miserables, I’d want to find a way to allow the audience to empathize with the people of Montreuil-sur-Mer and Paris. In this production, I never really did. And maybe that’s not what the Village audience wants. The Thenardiers work well, because the show makes us all Thenardiers, greedy for more spectacle, and taking advantage of the story in order to get what we want. But the poor of Paris disappeared, crushed under the massive set.

Actually, there was one moment that absolutely achieved what I’m looking for: Victoria Ames Smith’s “Castle on a Cloud”.

Little Cosette, standing in a small pool of light, while the massive set receded into the even larger darkness, really felt alone. And when she sang beautifully, it felt like she was overcoming that isolation to connect with us. Maybe she was truly nervous to be on stage, or maybe she’s one of those rare children who can truly embody emotional acting, but when she sang, she was beautiful. The whole spectacle of the piece disappeared, and I was watching young Cosette stumble through the woods with a bucket alone on a mostly dark stage, and I was transported to my own woods, far scarier than any that could be built for a stage.

Production knew to get out of the way. The woods were made of trees I’ve walked among, not the trees of a highly-skilled carpentry team, and I wasn’t impressed. I was moved.

Tony Beeman has lived in Seattle as a writer, performer, director and software developer since 1998. In addition to performing, directing and serving as Artistic Associate at Unexpected Productions in Pike Place Market, Tony performs regularly with 4&20 Improv, Seattle Experimental Theater, and Improv Anonymous. He has taught workshops in seven countries. His Myers-Briggs Type Indicator is INFP.

Leave a Reply