In Part I, we defined Narrative, Plot and Story. In Part II, we explored the ways that an audience builds that story while experiencing that narrative. Here in Part III, I want to introduce five concepts that stem from the difference between the concepts that I think are still vastly unexplored by improvisation.

In Improvisation, The Audience Discovers The Story First

In our example, we explored a written narrative. In improvisation, neither the players nor the audience start with a story. As the player discover narrative, both the audience and the improvisers discover story together. In fact, the audience often discovers the story before the improvisers do: which is part of the magic of being part of the audience for a great improvised show.

Have you ever watched an improvised show and made some interesting connection, only to have that idea squashed by a performer who failed to see the offer? Some of this is simply the cost of an art form that relies on risk, but improvisers who try to put too much definition on what just happened run the risk of taking the audience’s story away from them.

Improvisers Should Always Leave Enough Room For Story

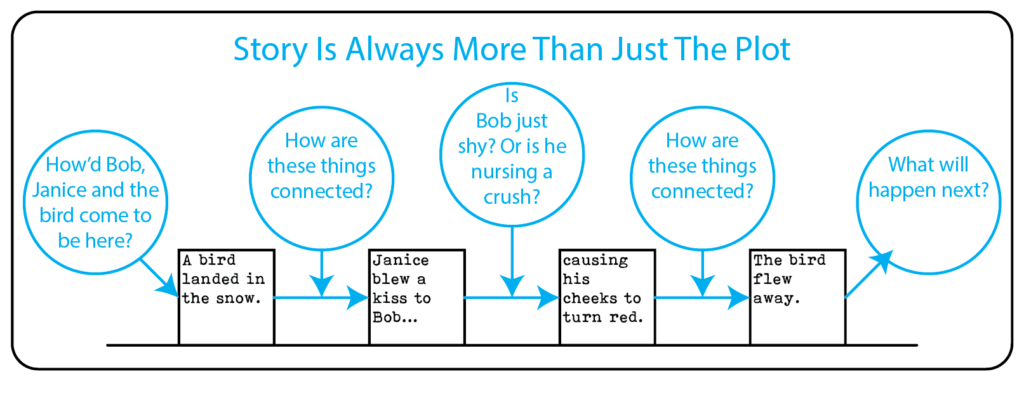

Every good story gives the audience enough plot connections to get them invested, but still leaves them space to build the rest of the story. Audiences like to sometimes guess at where a story is going. If the improvisers constantly rush through plot and explain to the audience exactly what is happening and why, the audience won’t have time to build story.

Ka Mua, Ka Muri

A scene probably starts at a point in the plot where there is interesting action, but rarely starts at the start of the plot. And the action will only be interesting (or have stakes) if we take the time to ask how we got to where we are.

Ka mua, ka muri is a Maori proverb (whakataukï) that is somtimes translated as “walking backward into the future”. In most improv, exploring the past tells us what about the plot is meaningful moving forward.

In fact, most plays, one-acts and sketches start closer to the end of the plot than the beginning. Improvisers who constantly advance will soon learn it is hard to retain audience interest, because stakes live primarily in the past.

The WAY that improvisers develop the narrative is often as important as the WHAT

Improvisers who limit themselves to one way of telling stories vastly limit the types of stories they can relate.

Style and Genres have a lot of lessons to offer improvisers, in terms of ways to approach narrative, if we take time to understand the narrative choices that a given writer or director makes and what the effect of those are.

Consider:

- Most Marvel Superhero movies provide most of the plot and explain most of the connective tissue. They don’t leave much room for interpretation. The dialog, visuals and music all tell us exactly how to feel, and by the end of the movie, the audience almost always understands why things happen and how characters feel.

- In Contrast, Film and Television Director David Lynch provides very little guidance in his narratives. Dreams, Shots of Stoplights and Ceiling Fans and Unreliable Perspectives are all presented with equal weight. It can be hard to even know what is plot and what is merely fact, in a Lynch-directed movie, and even his biggest fans often disagree on interpretations of the most basic elements of the story.

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle provides very little guidance through the first three-fourths of his narratives: Dr. Watson lays out plot items and facts without connection and the reader guesses at the story. But at the end, Sherlock Holmes and Watson remove almost all doubt about how the plot and facts tie together.

The Narrative Tools of the Stage Are Different Than In Other Mediums

We also need to understand the difference between the narrative tools that the stage offers, and how those offered by the medium of the source material.

Consider the story about Tuyen and Jackie: it contains a complicated setting (a cafe, a window, a sidewalk and a bus). It contains both feelings and memories which are never related through dialog.

How might we adapt that to the stage? Perhaps Tuyen relates this story as a monologue, or to another character: maybe we need to invent a therapist. Maybe we see Tuyen rush onto the sidewalk and hug Jackie, sharing her memory of the kiss and relating her loneliness since breaking up, only to discover it’s just a fantasy when the waiter interrupts the moment by arriving with the check.

We can look to playwrights for a lot of answers to how we might adapt other styles. Mamet’s American Buffalo suggests a way we might provide the narrative of a heist. Agatha Christie shows us how a way to adapt a chamber mystery with The Mousetrap.

Personally. every new genre or style I take time to study and perform present narrative opportunities in future shows that have nothing to do with the original author.

In future posts, we’ll spend some time applying these concepts more directly to improvisation!

Tony Beeman has lived in Seattle as a writer, performer, director and software developer since 1998. In addition to performing, directing and serving as Artistic Associate at Unexpected Productions in Pike Place Market, Tony performs regularly with 4&20 Improv, Seattle Experimental Theater, and Improv Anonymous. He has taught workshops in seven countries. His Myers-Briggs Type Indicator is INFP.